“What I don’t get,” says the dark woman with the husky voice, pouring out pale yellow juice into tumblers full of ice cubes, “is why we all bin sittin’ here buttoned up for three weeks now, listening to bug-static here and there and everywhere, and ain’t nothin’ really happenin’. I mean, yeah, I get the general idea. It’s guerrilla warfare, wear us down, but it’s like they’re wandering around totally lost. It makes no sense where they’re going. We probably wouldn’t have any problems, but it’s just that there’s so damn many of them looking for something. I ain’t never seen ’em bring in that kinda resources before. Usually, you hear ’em once if you’re lucky and bam! you’re up to your eyeballs in roaches. Then either you nail their goddamn nest until it smokes, or you just ain’t around to tell the rest of us what went down. You got any ideas, Drin?”

Drin frowns, and pulls chairs out from the table. “Oh, I have theories, but either they haven’t been panning out, or else it’s too soon to tell.”

“Oh, that sort. The kind you won’t know until maybe you’re a smokin’ hole in the dirt yourself, and it’s a little late then,” the woman says, pouring out lemonade with a steady hand.

“Yeah,” Drin says, and touches Emma’s forearm, looking at her. Her other arm is hanging onto the log doorjamb. Then he murmurs, “It’s been my suspicion that somebody meddled. Somebody who knows their records retention schedules for minor little items like taxes and title searches and that kind of limited era-specific, historically peculiar stuff. You know, somebody who kind of planned for this, before they left in a hurry?”

“It wasn’t me, I was off at my Aunt’s in Quirm,” Emma says, automatically. She’s read bits and chunks of Terry Pratchett out loud to the guys, some nights when there was nothing good on the tube, evenings when Dance was fed up with practicing. She does funny voices. It always makes them laugh.

Drin smiles.

The woman says, “Huh. Then it musta been your evil twin Skippy, huh? Heard some about her. I dunno, she sounds like serious bad to mess with.”

For some reason this comforts Emma, in an odd lopsided way, and she gives a wobbly smile.

Drin pulls his arm around her, and says, “Yeah, I suspect somebody pretty good at it set up some trails that’ll make the bugs cross-eyed.”

“You can thank Skippy for me, some day, when you run into ’em,” the dark woman says gravely, with just her eyes smiling. “I could use a little more that kinda planning round here, right? Well, unless that somebody outright edited themselves some handy bits of reality, out there on the theoretical fringes. Preacher can tell you stories to make your nails frizzle up. He says there ain’t no free lunch out there, either.”

“I expect Preacher’s right,” Drin says quietly, looking at Emma.

Emma wipes sweat off her forehead, lets go of the doorjam, and nods that she’s all right.

At the counter, the tall dark woman waves, and Billie Dean bobs his head to her and picks up six of the tumblers and carries them away into the front room.

They lost Dance in there, where the banjos and violin cases are stacked. She can hear Fozzie burbling away, the noise of cases being snapped open and shut, and little snatches of music. Sometimes it’s Kentucky-style picking on a mandolin, and sometimes it’s one of the Russian composers being dramatic on a violin. Typical, she thinks, that Fozzie would like a tone poet like Rimsky-Korsakov, when he claims he doesn’t actually play a lick of music himself.

Emma hears laughter, and then Dance’s hands are testing out familiar tunes on a banjo, and somebody else is challenging him on a guitar, and then there’s general country-style mayhem with a lot of bent notes and wailing harmonics.

“Well, damn,” Dance says then, easy and amused, “If I’d’a known you were gonna do that, I’d’ve brought my serious slides,” and it makes them laugh in there.

“Is it cheating to bar with your tail like that?” a teenager’s voice demands.

“Dunno,” Fozzie says, chuckling. “He ain’t had it very long. You’ve had your good ol’ slide tubes a lot longer than that. Is that cheating?”

The teenager grunts, and runs through some picking practices. Then he says, “So you need to exercise your new tail and stuff, get used to it yet, right, Dance?”

“That’s right,” Dance says, and tries repeating some of what the younger guy’s instrument has been doing. It sounds subtly clumsy. “I might be better at it after a day or two, I’ve been off on the road, not practicing any licks. I’m overdue for some serious fingering drills.”

Emma can feel her shoulders relaxing. Dance is a performer. He knows exactly what to do with an audience, and with younger musicians. He says something in there, and they can all hear Fozzie roaring with laughter. Emma feels Drin pat her arm lightly, reassuringly.

“Take a load off, your dogs must be barking like mad,” the dark woman advises Emma, gesturing at the chairs.

Emma sits down at the big scarred wooden table, blinking at the woman. Drin sits down behind her, and rests his hands on her, still for a moment. She sighs, leaning back into it. She feels Drin’s hands start stroking her neck and shoulders and lower back, cautious of her. He’s very aware that his touch might get irritating if it’s a bad migraine-sort of ache setting in, like a storm. She leans into his hands, letting him know it feels good.

Emma blinks as Fozzie’s old lady carries over a waitress-load of full tumblers and sets them down on the table. She holds one out to Emma, another to Drin. Men, women, and children wander through. They take one of the tumblers, grin at the woman, thank her, and wander out again. Some of them are the blocky-headed people whose eyes don’t track so well. They smile shyly, showing gaps where some of their front teeth ought to be, and they lisp when they talk. They seem to be clumsy, and slow, and the woman lifts a tumbler for each one, putting it carefully into their hands and making sure they have a good grip on the tumbler before she turns them to go out again.

“We can’t thank you anywhere near enough–” Emma begins.

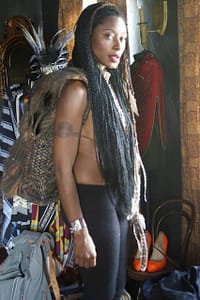

The woman waves it off with a long swift hand. She is tall and thin with long dreads threaded into red Chinese bone beads. Her face has a classic Seminole nose and broad cheekbones under skin nearly as purple-black as the dragon design beaded around the full yoke of her red satin western shirt. It makes her look like a backup singer in an ambitious reservation country-western band. There are no extra appendages or attachments or joints or things tucked away in the shirt. If she has them, then she keeps them put away, in something like that zero-g closet that Drin talked about, the one where Dance kept his tail stored. That is, the closet that he fell right out of.

Emma is pretty sure Lacey has something tucked away there. She’s not sure she needs to know what it is. Some dusty perfume on the woman reminds her of Dance, and makes her wonder, the same as she wonders about the odd bits of information flashing up on the furniture, the stoneware jugs, the big old kitchen pots. Emma does not want to ask herself how she knows all this information is embedded into the objects she’s looking at.

Emma tells the woman, “Fozzie probably said earlier, I don’t know. My name is Emma–”

“Call me Lacey,” the tall dark woman says, picking up a cheap plastic knitting bag from a chair nearby, and putting it down on the floor beside the remaining empty chair. “I hope you don’t mind if I work some rows on this baby blanket, it soothes my hands, and Lord knows that baby ain’t gonna wait around for me to have time.”

“Show it to me?” Emma asks, knowing from her experiences working at the library that the handwork will be soft and beautiful and they will both feel better talking about that instead of all that crap building up out there in the heat and the dust, like the thunderheads bulging on every horizon beyond the trees. She picks up her icy glass and sips.

The lemonade is tart, just slightly sweetened, with the same herbal extract that Drin always brought home from the natural foods store for Dance. “Stevia,” she says, surprised, and pleased to be able to recall, through the pain in her head, both the taste of the extract and the way the herb itself looks. “Dance likes to grow it in the garden, he nibbles on it all the time,” she says.

“It’s a real blessing for diabetic folks, let me tell you,” Lacey says. “Dance sounds like quite a guy.” She lifts a warning finger. “No, don’t bother, you’re both so far gone on him I ain’t gonna get sense outta you two. Yeah, I’ll help him get back on some kinda sensible diet, if I gotta cram bonemeal down his throat myself. Don’t know that taking some baseline blood samples would help much, when you got nobody else to give any comparison to it. It’ll be interesting to drag him round our grubby little garden plots, see what he has to say. Or wants to chew on.”

“He’s been mostly growing herbs. He’s as bad as this guy,” Emma says, and pokes Drin’s arm with her thumb, “taking on more projects than he can finish. He loves to putter around in the dirt, but he never has — he never had time, with the orchestra.”

“Yeah, like any other performing gig I’ve ever heard of,” Lacey agrees. She spreads out an expanse of fluffy pinky-red crocheting along the edge of the table, frowning at it. She’s made about a yard of delicately netted loose spaces barely held together by the soft, plushy yarn.

“That’s going to be nice and warm in the winter, wrap it up as a middle layer,” Emma says. She smiles and lifts a corner in her hands, petting it. “So soft!”

“You do any handwork yourself?” Lacey asks.

“Sometimes, but mostly I kibbitz when other people are slaving away,” Emma says. “I’m good on the advice end of things.”

Lacey smiles back. “I’m good on hearing advice,” she says, and taps a stretch of it. She lifts it around, gazing at it critically, and brings out a little ruler and measures one part against another. She clicks her tongue. “Now look at that, I got distracted on watching those damn NASCAR races last week, my gauge is way off there.”

Emma touches it, and smiles. “Do you think the baby will notice the gauge is off?”

The woman snorts. “No, but the baby’s Granma will, trust me!” Lacey sighs, and she starts yanking out rows of her own work, winding the yarn back onto the fuzzy ball it came from. It’s full of wavy crinkled stretches, as if Lacey has been crocheting and ripping it out many times.

Emma holds out her hands, offering to wind it onto the ball, and Lacy hands it off and yanks in earnest.

Lacey nods at the remaining drape of feather-soft netting. “Well, now you know why I picked my CB handle,” she says, and makes a face. “Even though I spend a lot more time fighting dirty laundry and kicking lazy boy butts to shovel piles around, honestly. But that’s kinda like handwork too–you just keep it moving, whatever you do.”

“Sounds like a wise idea to me,” Drin says then, smiling a little by Emma’s shoulder. “You got too many boys wandering around in one place to let ’em get bored. Keep those muscles moving, that’s my advice.”

“It was back when you bought this place to begin with,” Lacy says, looking up at Drin. Her posture is relaxed, easy. “I remember you tellin’ Fozz to just keep those juggling balls in the air, just keep it movin’ all the time.”

He chuckles. “Seems silly now, tellin’ that to a guy who decided to be a trucker.”

“He’s still a lousy juggler,” Lacey says, with every evidence of tolerant fondness in her voice.

===

Challenge: Cornered