When he wakes up, in the dark, his body is rocking back and forth at some indeterminate height, on inadequate padding, and something is brushing at his hair. He blinks, twists a little, and relaxes. He is in the upper berth of a sleepover cab swaying on a fairly rough road, with the roar of the reefer going about five feet from his ear, outside. Somebody has shut the little curtain so he isn’t blinded when he wakes up. The hem is touching his head.

He suspects the somebody is the person whistling cheerfully along with the Preacher’s voice, slightly crackly, on the local broadcast station. The Preacher is singing to the universe, via local radio, in a nice basso, “Onward Christian Soldiers.”

“Hey, Drin,” Fozzie says, to the creak of the driver’s chair, and the rig sways on a corner. “You feeling hungry yet? Got some pop down here in the cooler, if you’re thirsty. Just be careful crawling down. Preacher’s giving your head a massage that hard can make you dizzy, sometimes.”

Drin curls up, clutching his head. Covers his eyes.

“You let me know, I got some fries left here,” Fozzie says, with the faintest twinge of worry in his voice.

“I’m okay,” Drin manages, and knows he sounds funny. It’s not all there, it hasn’t all come back. But enough to hurt like hell. He doesn’t bother to fight it. Let the water run down his face, what the fuck does it matter? Fozzie’s seen it before, God knows, and Preacher sees it all from the inside, like no confessor on earth.

He understands now what Fozzie meant. This time, when he made that long rough trip back down the Railroad, bringing along some of the most difficult rescue projects he’s ever brought to Fozzie’s horse farm, he was told that was it. That would be his last trip. The folks who were left back there, knowing they were in a position they couldn’t hold, knowing, too far up forward there, too close and too exposed near the Asian labs, the only ones left to help him, they insisted on scrubbing out as much of his memories of it all as they could. Forget, live out your life in in peace, at the end where the zoomorph people are freed.

Don’t come back again, they said, too risky, too much to be lost if you’re caught, and they have made it as close to impossible as they can. How the hell did they do that, without someone–or something–like Preacher Slick at hand to do it? Is there another like Preacher out there in the world? Can you make somebody like Preacher?

Much of it was too seriously smudged out for even a miracle man like Preacher Slick to recover the expertise that was once there, but the stains and the grief and the music of it are still there.

He was married, a long time ago. His wife’s face is gone, her name, what she liked to do, all of it; there is just the fact of how much it hurt to lose her.

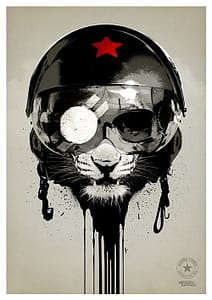

The military labs were never that secure, or that careful, or that bright, about keeping their modded creatures from contaminating the civilian environment. Offer any security gap at all, and the black market will find a use for it. Kiplings, the early prototypes were called, somebody’s romantic notion. Kipling himself thought war was a fun, romantic occupation, he never saw the real horror, or the waste, or the corruption. Aside from being a racist in the way that all of his generation was, of course–quite advanced for his time, really. The project leads who borrowed those names didn’t have the same excuse.

One of the last war-spec creatures grown in the contract labs ended up on the black market afterward. It was used idiotically, used in ways that drove it quite mad. Drin came out of retirement, and he killed it, a mercy. But not in time. That Shere Khan killed a lot of innocent people first.

He testified, with helmet-mounted video records. Talked about the Shere Khan, about how it killed his wife. Made no difference at all. Oh, they jailed a few scapegoats, they actually fined a few others, but it didn’t stop the trade at all.

The contract labs remain busy, years after the end of that unlabeled war. The labs have never stopped growing out things based on combat blueprints, at quite a nice market price, and washing their hands of it, just walking away from it, when something turns into the monster image that its new owners never acknowledged was there all along. He doesn’t believe the news reports of man-killing tigers in Asian provinces that are stripped bald to the dirt by too many people in search of firewood and too many goats and too many skinny cows. Those things were never tigers.

He’s never forgotten the inquiring yellow gaze of the first, the very first, of the Bagheeras he’s had to put down. Ever since, he’s been going in and rescuing the creatures he can, and killing the ones that nobody can handle, ever. Fucking. Since. Call it job security, for a retired military handler of zoomorphs.

And now those people, on the forward line, as Fozzie puts it, they’ve made it impossible for him to go back. Impossible to find his ass with either hand, in this context.

The folks fighting on their own over there, on hostile ground, with all the money against them, facing what comes out of self-determining factories that are building their own bug-mod assembly lines and their own bug-mods and their own entirely alien agenda.

Go home, those people said, and if you can’t forget about this, then stop the Bugs from growing out in your own area, before they can get this far out of control. You have more tools than we did.

Fozzie’s horse farm, at the end of the Underground Railroad, is where lost wild zoomorphs drift in on the tide and get clean clothes, some food, and attempts at direction to some kind of new life. Not all of them are creatures that Drin brought back with him, rescued from Third World labs. Very few of them are children of zoomorph people, either. Most of those women couldn’t carry to term if they had the best care in the world, and most of the men are infertile at best.

But the bugs, man, Fozzie says the bug-mod are testing his perimeters all the time. They’re coming from somewhere. Fozzie and Preacher said there’s scam-artists out there, cheap black market suppliers running bug troop labs, impossibly, right out there in American swamps.

That swamp sounds like a pretty busy place, what with the nutjobs protecting their pot and their meth labs with booby-trapped rifles and the wingnut militia compounds with barbwire fences and highly illegal artillery, and the bug labs, with their greenhouses full of green sarcoboxes in the back, where they don’t let anybody look too closely.

Some of the people Fozzie rescues aren’t Kiplings in any form, they were accidents. By-products. They’ve come out of the woods like feral dogs, fearful and covered in ticks, unable to tell anyone why they suddenly started growing wolf teeth in their long jaws, or a nose capable of outdoing a bloodhound, and no memory of how far they’ve hiked through the nights, or quite where they were coming from in the first place.

“Over the mountains,” they say, and tell you about drinking from park fountains along the Appalachian passes. Their families sometimes show up with them, even, talking about drifts of pink fog swirled around by almost-silent choppers running sweeps over the trees, at night, when everybody is asleep. Dumping stuff that didn’t work, Fozzie says grimly.

Some battles, there is no retirement. You just get tired.

“Yeah,” Fozzie says to the silence, as if he does know what it’s like. “You let me know.”